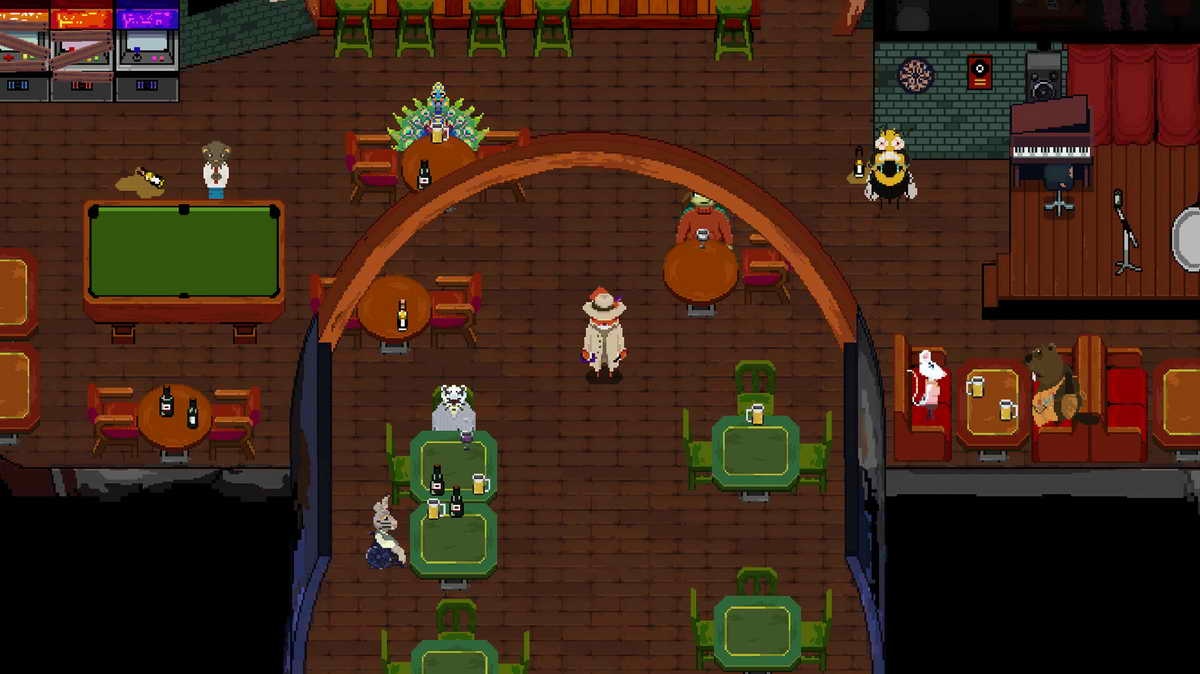

Gareth Owens – a onetime film-and-TV writer who cut his teeth with studios from Aardman to Pinewood before founding Wise Monkey Entertainment – has spent the last few years turning a lifelong love of British whodunits and absurdist comedy into something delightfully strange: No Stone Unturned, a comedy‑noir detective RPG game that casts an amnesiac squirrel, Detective Cox, as its hard‑boiled protagonist and stitches together murder mysteries, bespoke mini‑games, and theatrical puppetry‑inflected performance into a single, mischievous package. The game wears its influences proudly – Columbo and Jonathan Creek meet surreal animal farce – but it’s also unmistakably Owens’: part escape‑room puzzle design, part cinematic storytelling, and all pointed, playful weirdness aimed at making players laugh while they peel back a much larger mystery beneath the village’s quaint surface.

No Stone Unturned feels like a collision between classic British murder mysteries and absurdist animal comedy. When and how did that tonal balance click for you?

A blend of Murder Mystery and Absurdist Comedy is exactly where No Stone Unturned sits. I found that quite naturally growing up with 2 police detective parents watching Columbo, Johnathan Creek or Fawlty Towers on VHS. I think I’ve always had that tone itching to come out, this is just the first time I’m really letting it out.

Detective Cox is a soft-boiled, amnesiac squirrel, which is both a noir cliché and a subversion of it. How did his personality and backstory evolve during development, and what does making him an animal allow you to do narratively that a human detective would not?

It’s interesting, there are lots of mysteries inside No Stone Unturned, one of those being the very real questions of why are these animals talking? Why do they act like humans etc. There’s a lot more to uncover there. But it all started with the core premise “Why did the chicken cross the road?” Which in turn came from trying to pair the setup of a joke with the setup of a murder mystery, I really like starting ideas off with puns, double meanings or patterns in speech.

Was there a particular moment where you realised a joke, mystery beat, or emotional payoff worked better as gameplay than it ever could have as prose or script?

Definitely, I can’t spoil the ending of course, but the gameplay of the final final boss moment is one of my favourite gags ever, and it only uses gameplay to convey the joke, with no words spoken. I love using gameplay to subvert players actions as much as I use story to subvert players expectations of characters.

The game leans heavily into a wide variety of mini-games, many of which double as punchlines. How did you ensure these moments feel purposeful rather than like distractions from the central mystery?

Every mini-game either blocks the player from story progression or gives them a new useful collection item etc. We make a lot of bespoke work, mini-games that will only appear once. As I come from film/tv/escape rooms, I built this game a lot like a movie mixed with an escape room, I didn’t have all of the bad habits the games industry has somehow learned around storytelling and player retention/engagement.

On the surface, this is a quaint village full of troubled animals, but there’s a clear sense that something much bigger is unfolding beneath the jokes. How early did you know the story would scale beyond individual murders into something more existential?

When I first created the story I wrote it as a loose outline of a trilogy, so I always knew there was a lot more to hide underneath everything. I can create a plot outline in an evening, but the exact depth of No Stone Unturned is something that has been built and shaped over the last 3.5 years in order to make sure its the best piece of work it can be. I’m not only trying to make players happy, I’m trying to prove to myself that I’m as good at this as I think and make myself laugh too.

British humour is notoriously difficult to translate internationally. Were there jokes or cultural references you had to rethink to ensure they landed for a global audience?

In truth I thought about it in the complete reverse, I would argue Absurd British humour is something that can be sent all over the world – because it marks so clearly the difference between what is said and what is meant. And even in cultures where that is not the norm, it makes stories incredibly interesting. Although I’ll only be providing subtitles on launch, no dubbing, so the jokes will land as written and intended – at the end of the day this game is a message from me to the rest of the world, and I speak English.

One of the more unusual parts of this project is your collaboration with the Henson Company, including the fact that you had to take puppeteering lessons first. How did that connection come about, and what did learning puppetry teach you about performance and character?

Before this I worked as a ghostwriter for Murder Mystery Film/TV, while doing that work I was able to get the email for a relevant team member of the Henson Company from a colleague who worked with them, and over the course of a few months we agreed on working together, making a Detective Cox puppet. And I hope we’ll get to work with them more in the future, I love their stories and the worlds Jim created. They are excellent at what they do, so learning how to control puppets was very interesting but one of the parts I didn’t expect was just how heavy they are! It’s a real workout, anyone that can perform as a puppet for longer than 10 minutes, I have to believe there’s just something different about those humans, it’s incredibly difficult especially when you want to articulate emotions.

As someone making the leap into video games, what has been the hardest part of wearing so many hats at once, and what has been the most rewarding?

I would say the hardest part of doing so many things is keeping track of it all, I often rely on my own mind and memory, meaning when things get heated and busy, I can forget things – and I absolutely hate systems that are meant to make that easier, my neurodiversity doesn’t allow for that kind of helpful structure, I need to exist in chaos and urgency for anything to actually get done. The most rewarding part of the process is the people, I really like the people I’ve brought into Wise Monkey, we have a team filled with devs who are truly born to do this, they understand the mission and they understand the style, they’ve done such a good job taking on something I thought was so personal and individual to me and seeing themselves in it, the same way the audience response has been so nice, even for a game that isn’t out yet!